Get big things done (in data science)

The book ‘How Big Things Get Done’ by Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner is an excellent account which studies some famous projects and analyses the differences between successes and failures.

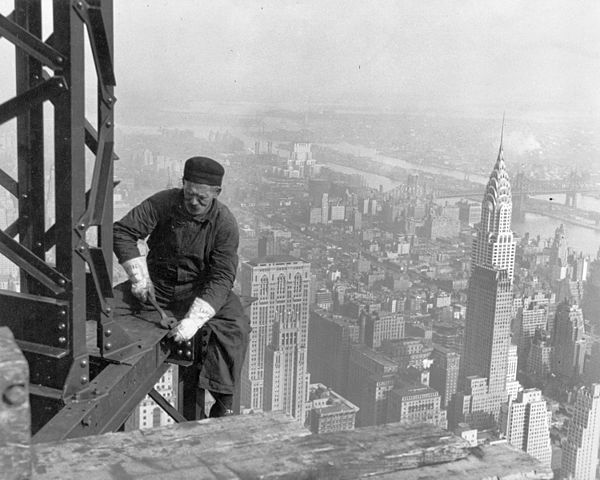

The book focuses on very large projects mostly in construction, including the Empire State Building, and Heathrow Terminal 5, but it also has other examples from other industries such as film production. In the past I worked in consulting on major government projects and many of the experiences he relates from some of those projects rang true to me.

One of the great success stories is the Empire State Building. Amazingly, it was built on budget and ahead of schedule, because it followed a particular set of principles, which are applicable to other projects. In this article I’m going to highlight a few of those principles, and some practical ideas on how to apply them to data science projects.

It’s an excellent book which I would recommend reading in full - it’s fairly short and written in a clear and engaging style. I can’t cover all of the ideas but I’m going to highlight three in particular.

Think slow and act fast.

The first part of this is that it’s worth coming up with good and robust plans which really thoroughly consider how things can go wrong. Yes, there are examples of detailed plans which capture the wrong things, and it’s often said that “no plan survives contact with the enemy”. But I think having no plan at all is a bad idea.

I think the ability to anticipate and plan ahead is extremely valuable – if I’m out traveling you can see who has anticipated that they might need to carry a bottle of water and a raincoat, and the people who haven’t. On projects, this might mean identifying the likely blockers and dependencies ahead of time - maybe it’s data access permissions, or following some lengthy approval process. This can be started early, and save time later. So I think that trying to imagine how things will go and create something like a plan is really useful.

The second part of this is acting fast. Flyvberg and Gardner assume projects begin with a planning phase and then move to an acting / doing / roll-out phase. They make the really interesting point that the longer that a project goes on for, the more likely that it is that things will go wrong. If you’re spending five years rather than one year making a building, then that significantly increases the risk that an important project leader might move on, a supplier might go bust, or some other external factor means you can no longer get some raw material. While it’s hard to plan for all unknowns, the longer a project goes on for, the more you are exposed to them. Also, the roll-out phase is typically more resource-intensive than planning - and so wasted time here is much more expensive than in planning. I can really see the arguments for investing time in thorough planning, and then getting that back, and more, through really fast execution.

I think one data science learning from this is that it’s really worth investing time setting up tools and templates at the start, and things like making feedback loops and automated testing as fast as possible. Last year I developed a personal project where I spent a lot of time building and running docker images, had to wait at least fifteen minutes for deployment feedback on each change. Even though I knew how to use docker-compose.yaml, I’d never bothered to invest the time because it felt quick to fix on the fly. But thinking more about fast execution, I realised that typing docker commands was taking up lots of time each iteration, and that I could run tests locally before deployment. Once I’d set up the docker compose and set up local testing, it felt like much less friction in the development process and I wished I’d done both earlier.

The benefit of experience

The authors identify that often people who don’t have relevant industry experience, but who do look generally impressive, end up leading major projects. I can see the argument that leadership skillsets are general, but if you’re leading quite a technical project, like building a new train line, then maybe it will be really helpful if the key leaders have a background in the rail industry. It turns out lots of industries have quite specific knowledge and common pitfalls that experienced people can avoid. It sounds trivial but I think there is an implication.

It might be that the same applies in data science. Consider hiring for an NLP role. Let’s imagine there are two final candidates: one has very impressive computer vision experience, but another candidate has less experience but more of an NLP background. It’s tempting to choose the computer vision whizz, but if you want to ship an NLP project faster, then it might be better to choose the NLP person who’s spent hours resolving issues with spaCy installations, and tinkering with the transformers library.

Back to the book. Another really interesting, and more philosophical, direction that the authors go in is that we could see technology as embedded experience. If you consider even a simple teapot, it has still gone through many thousands of years of iterations and experience. The physical form is the product of learning from that experience – maybe the handle should be larger, the spout should be smaller, and so on. So we could see technology, both physical but also intangible tools like python libraries, as the product of experience. And more experience is better.

A clear application to data science is that it’s better to use tried and tested tools. A common frustration in data science is using fancy experimental large language models when they aren’t required - I hear you, and I’ll come back to this later. Another way to take on this advice could be seeking to use popular and experienced tools - maybe a particular AWS Docker deployment pattern is looking a bit old fashioned and lacking the latest functionality, but maybe it is better to stick to the classics if what you care about is getting things done.

Think from right to left

The final idea I want to cover, and I think the most important, is thinking deeply about what the goal of the project really is. Flyvberg and Gardner describe this as thinking from right to left - project plans start from the left and proceed across the page to a goal on the right. This assumes we need to do everything on this page to get to our goal. But instead they ask: what really is the goal on the right? And, what is the best way to get there?

Let’s take a real world example - let’s imagine a person who wants to lose weight, and as a result they are doing some detailed analysis of which carbon fiber racing bike they should buy. They find the research very engrossing and mentally stimulating - you could imagine them spending time reading up on the differences between various bikes, putting all sorts of metrics and numbers in a complicated spreadsheet, maybe even visiting bike shops and going for test rides. But why are they really doing this? Without having a goal in mind, it’s easy to fool yourself into thinking that you’re doing something valuable.

Maybe this person already has a perfectly good bike, perhaps even a very nice racing bike, which they never use. Maybe more pressing issues are that they smoke 20 cigarettes a day, and eat an extra large cheese pizza every day. It doesn’t matter how complicated their spreadsheet is, if there are much faster and cheaper routes for them to get to their goal. Perhaps this person would like a new bike - and that’s fine - but they shouldn’t delude themself into thinking it achieves their goal.

At work it’s easy for projects to fall into the same pattern. People have meetings, write code, do all sorts of clever things, but if we can’t tie it back to achieving some goal, then they can end up being like expensive bikes that never get ridden.

One very insightful section in the book looks at some projects that deliberately violate these principles. The reasons are partially political - people want to do grand, ambitious, and risky projects because they think their success will improve their reputation.

It also might be that there are other implicit goals for a project. I said I would come back to questionable uses of large language models. In data science, rather than the model improving a metric, maybe the organisation wants to be seen in the market to be using some new tool, like a large language model, and so it’s partially driven by external perception. Or perhaps the project is partially to build experience in the team, or as a self-development project. I think implicit goals can be ok, but we need to up front with leadership about what the goals really are.

The plus side of this is that once we have our goals front of mind, it makes day to day decision-making and prioritisation much easier. I also find it helps with motivation. The book describes the sense of mission that staff building Heathrow Terminal 5 felt - people laying tiles felt their work was a step towards the project’s goal. That enthusiasm helps spur everything else forwards. I think it’s time to get excited about the goals of our projects and think daringly about the best way to get there as possible.

Summary

- It’s worth investing in things that help you develop faster later on. For example: repo templates, automated testing, using docker compose, and using images that rebuild automatically

- If all else is equal, choose well used tools. This might mean choosing pandas rather than polars, AWS Sagemaker rather than Google Vertex AI.

- Think deeply about the project goal. Is this project definitely the best way to achieve it? If you can align activities with the goals, then everything else should fall into place easier.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: